Arms

Intro

Arms can be a cool way to move pieces vertically and are often lighter than an elevator.

Concepts

4 Bar

Virtual 4 Bar

Weighted Virtual 4 Bar

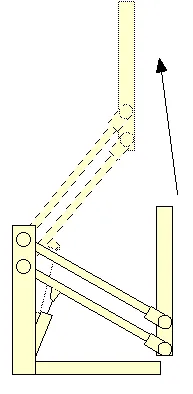

4 Bar

Relevance: When placing a game piece at different heights, it is often useful if that piece keeps its current orientation. A 4 bar can help achieve this.

A 4 bar is a type of linkage that consists of (you guessed it) four bars. When connected at movable joints like in the image below, the output member stays parallel as the beams form a parallelogram.

4 bars can consist of beams that are not of corresponding length. In these cases, the motion of the system is more complex.

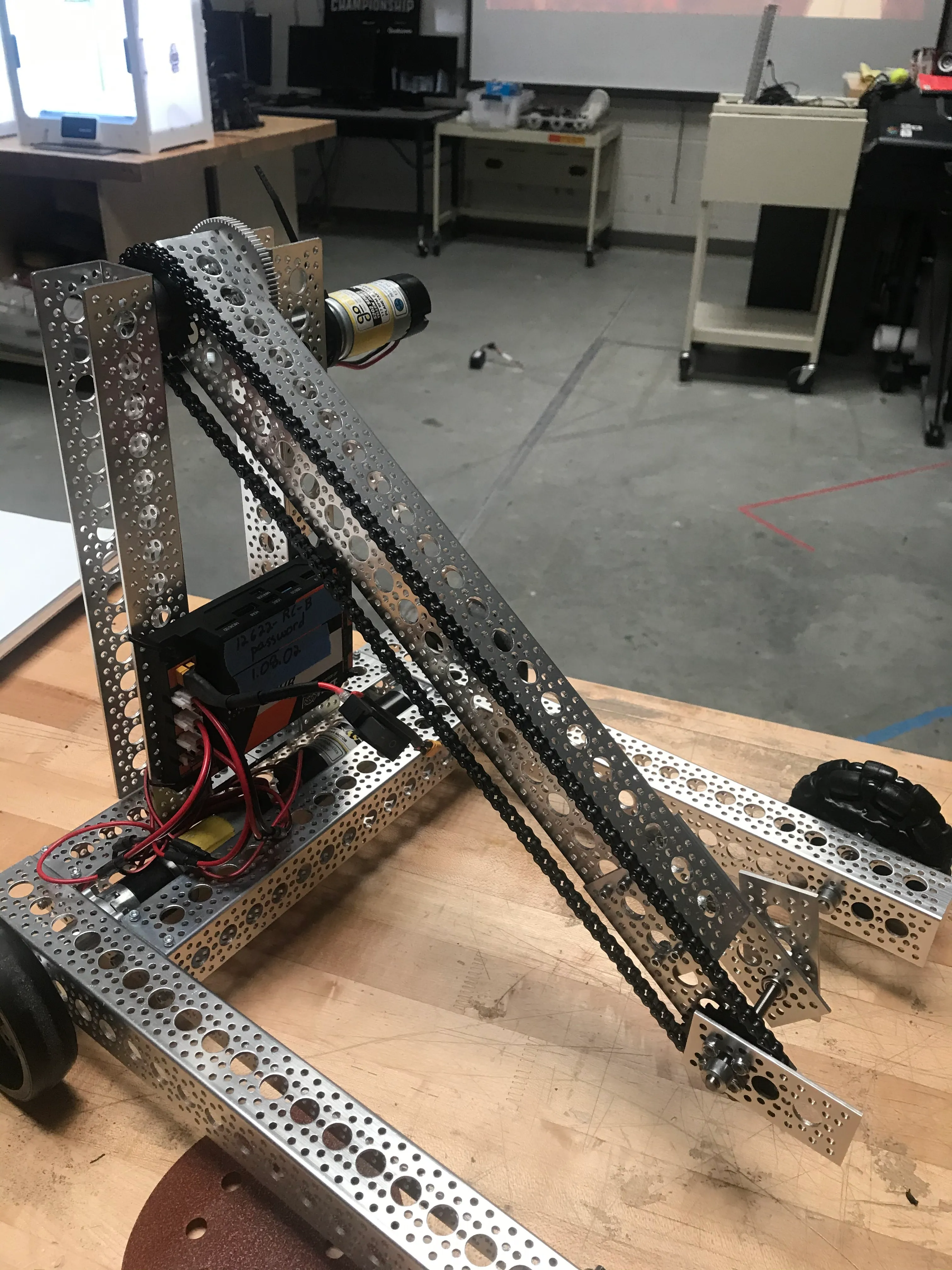

Virtual 4 Bar

Relevance: The 4 bar from the previous section is pretty useful, but it can be limiting in size and range of motion. Virtual 4 bars fix this.

A virtual 4 bar replaces the parallel bars with a loop. This loop is typically made of chain and is connected by sprockets. When designed with clearances in mind, virtual 4 bars can go past vertical—giving the virtual 4 bar a larger range of motion.

Key points of a virtual 4 bar:

- the sprockets must be the same size

- the base sprocket must be fixed

- the sprocket at the wrist must be free to rotate

Weighted Virtual 4 Bar

Relevance: A solution to when a manipulator needs to be in two different positions at two different heights.

What I (Michael Menezes) am calling a “weighted” or “unbalanced” virtual 4 bar is a virtual 4 bar with different sized sprockets. When virtual 4 bars use sprockets of the same size, they keep the wrist sprocket in the same orientation in relation to the ground throughout its motion. When sprockets have different sizes, the wrist sprocket will rotate relative to the ground.

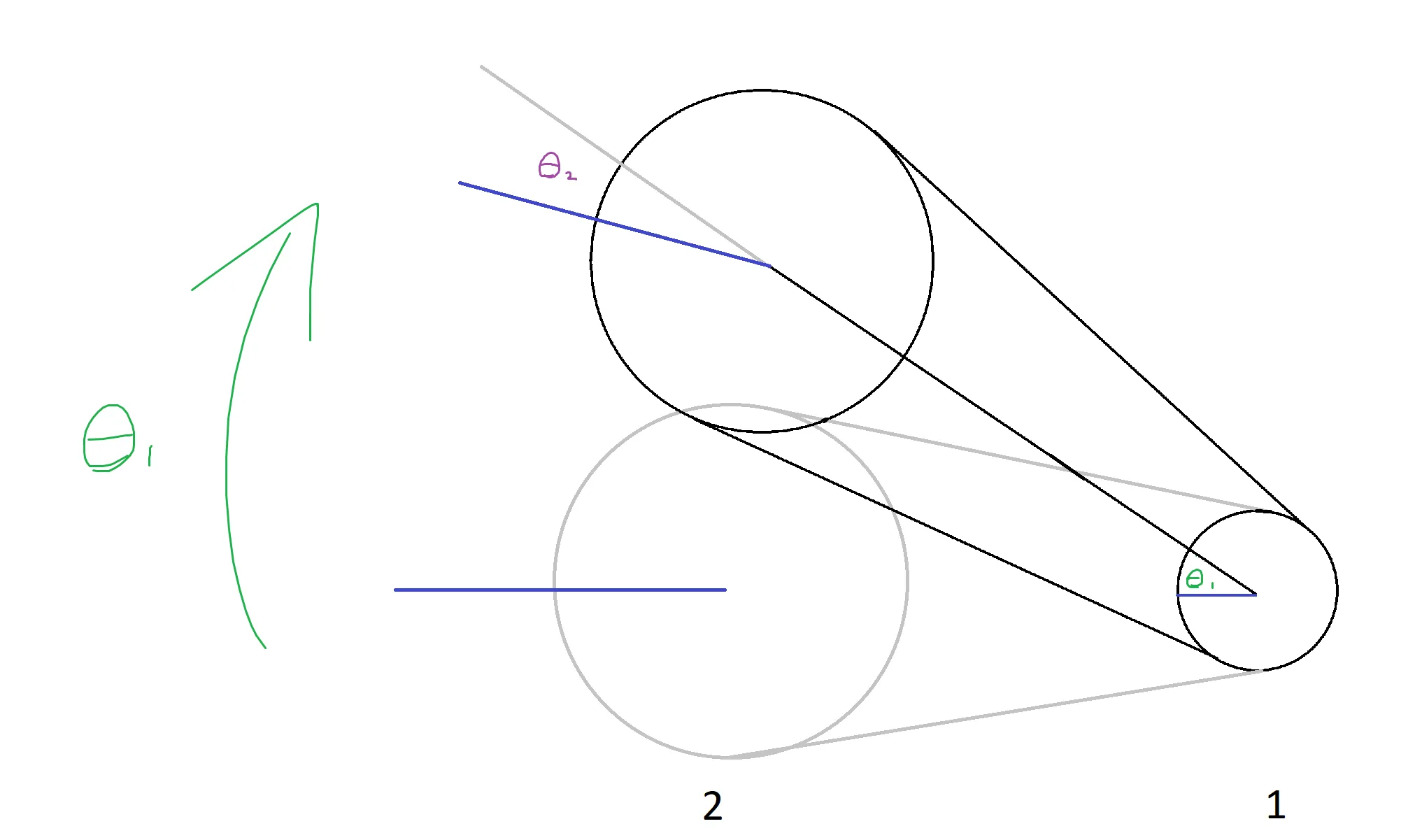

Let’s take a look at the math.

When sprockets are chained together, they act similarly to gears (except they don’t counter rotate). What I mean is that chained sprockets have the same tangential velocity $v$ but differing angular velocities $\omega$.

By inspection of a standard virtual 4 bar, it may seem like the sprockets are not rotating when in fact they are rotating relative to the bar that connects them. The diagram below demonstrates how a weighted 4 bar would function with angles measured relative to the bar.

Let: the base sprocket be indicated by 1 and the wrist sprocket by 2 $$v_1=v_2$$ $$r_1\omega_1=r_2\omega_2$$ Integrating with respect to time yields: $$r_1\Delta\theta_1=r_2\Delta\theta_2$$ $$\Delta\theta_2=\frac{r_1}{r_2}\Delta\theta_1$$

Put into words, this means that the amount we rotate the base sprocket will rotate the wrist sprocket an amount that is proportional to the ratio of their radii relative to the bar.

That’s great but what about relative to the ground? We can see on the diagram that the angle of the bar is defined by $\theta_1$ thus the angle of the wrist relative to the ground is $\theta_1-\theta_2.$

EX: Doing the reverse calculation.

I want to design an arm that can:

- Position a game piece level to the ground when the arm is horizontal

- Position a game piece at 45 degrees above the horizontal when the arm is at max heigh (vertical)

Alright, our first constraint can be taken care of simply by fastening the manipulator to the wrist while the arm is in that position. The second constraint gives us the angle the wrist should be to the horizontal as 45 degrees $\theta_1-\theta_2$ and the angle the arm makes as 90 degrees $ \theta_1 $.

So: $$90 - \theta_2=45$$ $$\theta_2=45$$

We can plug this into our formula to get: $$r_1\Delta\theta_1=r_2\Delta\theta_2$$ $$r_1(90)=r_2(45)$$ $$r_1=\frac{45}{90}r_2$$

We do not have enough information to find the exact tooth counts but we do know that the base sprocket must be half the size of the wrist sprocket. The exact size can be whatever is most convenient like maybe 50 T and 100 T or 20 T and 40 T, etc.