Gears

Intro

Gears are a simple yet effective way to transfer rotational power. Gears are used in all sorts of mechanisms from drivetrains to jointed arms and elevators.

Concepts

Positioning

Relevance: Gears that are positioned too close together can bind up and cause teeth to wear away faster.

Gears have an intrinsic property known as diametral pitch dp. The diametral pitch is defined as the the number of teeth on a gear T divided by the pitch diameter D. Intuitively, diametral pitch can be understood as a conversion factor from diameter to tooth count. The pitch diameter is the diameter of a circle that intersects the teeth on the gear in the middle of the tooth height (technically it is when the tooth width is the same as the spacing between the teeth). Pitch diameter is easier explained with an image:

Finding the diameter of a gear from dp: $$dp=\text{teeth}/\text{diameter}$$ $$dp=T/D$$ $$dpD=T$$ $$D=T/dp$$

The recommended distance rd between gears is the center distance cd plus 0.008 inches. $$cd=\frac{T_1+T_2}{2dp}$$ $$rd=\frac{T_1+T_2}{2dp}+0.008$$

Reductions

Relevance: Gears can alter the speed, direction, and torque of an input. Understanding reductions provides insight on how well a system can perform a task.

Rotational Velocity

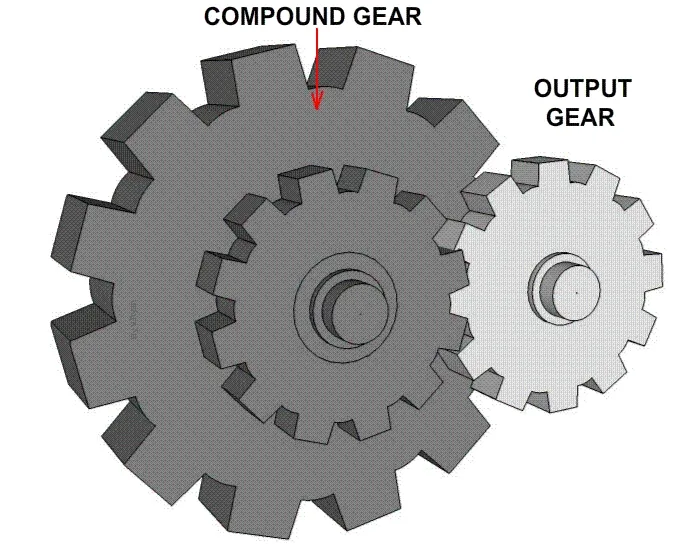

Gear are typically arranged in two ways: side by side, or stacked.

When gears are stacked, they have the same rotational velocity $\omega$. When gears are side by side, they have the same tangential speed $|v|$.

A reduction occurs when a small gear “drives” a bigger gear aka. a small gear is next to a bigger gear.

An upduction is the opposite of a reduction, a larger gear driving a smaller gear. This is inefficient and is typically something we want to avoid.

Deriving the relation between side by side gears:

*Assume: $T_1$ is the smaller gear

*$r=\text{radius}$

$$v=r\omega$$ $$r=\frac{T}{2dp}$$ $$\text{since: }v_1=-v_2$$ $$r_1\omega_1=-r_2\omega_2$$ $$\frac{T_1}{2dp}\omega_1=-\frac{T_2}{2dp}\omega_2$$ $$T_1\omega_1=-T_2\omega_2$$ $$\omega_1=-\frac{T_2}{T_1}\omega_2$$

Deriving the relation between stacked gears:

$$\omega_1=\omega_2$$

In a gearbox, the relations between gears typically alternate.

EX: Imagine a gearbox with four gears. The first gear is small and is directly driven by a motor. The second gear larger and is adjacent (side by side) to gear one. The third gear is another small gear but is stacked on top of gear two. The fourth gear is adjacent to gear three. $$\omega_1=-\frac{T_2}{T_1}\omega_2$$ $$\omega_2=\omega_3$$ $$\omega_3=-\frac{T_4}{T_3}\omega_4$$ $$\omega_4=-\frac{T_3}{T_4}\omega_3$$ $$\omega_4=-\frac{T_3}{T_4}\omega_2$$ $$\omega_4=\frac{T_3}{T_4}\frac{T_1}{T_2}\omega_1$$

As you may have noticed, when gears alternate, the relationship between the angular speed of the first gear and the angular speed of the final gear are directly proportional. The coefficient on $\omega_1$ is equal to the product of the driving gears’ tooth count divided by the product of driven gears’ tooth count. $$\omega_n=\omega_1\prod_{i=1}^{n/2}-\frac{T_{2i-1}}{T_{2i}}$$

Note: In a gearbox with an alternating structure, the number of stacked gears $n/2$ is given a special name as the “number of stages.” Thus, the gearbox from the example above is a two stage gearbox.

Torque

The benefit of using gears to reduce the speed of a motor rather than using less electrical power is that a gearbox will increase the torque of the output in exchange for the lower speed.

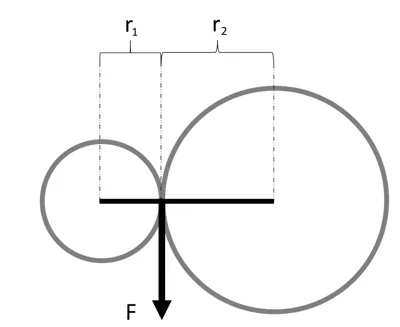

EX: Deriving the relationship between gears and Torque:

**Let: $\tau_0=\text{motor torque}$*

*Vector notation will be omitted to improve readability

*The following example continues off the previous one

$$\vec{\tau}=\vec{r}\times \vec{F}$$ $$\tau_0=\tau_1$$ Since adjacent gears are touching at a point: $F_1=F_2=F_{12}$

$$F_{12}=\tau_1/r_1$$ $$\tau_2=-F_{12}r_2$$ $$\tau_2=-\frac{r_2}{r_1}\tau_1$$ $$\tau_3=\tau_2$$ $$\tau_4=-\frac{r_4}{r_3}\tau_3$$ $$\tau_4=\frac{r_4}{r_3}\frac{r_2}{r_1}\tau_1$$

From this result, it is apparent that torque follows a similar relationship to that of angular velocity except that the coefficient on the input term in the torque equation is the reciprocal of the corresponding coefficient in the angular velocity equation.

Generalizing the formula found in the example: $$\tau_n=\tau_1\prod_{i=1}^{n/2}-\frac{T_{2i}}{T_{2i-1}}$$

Inertia

Relevance: When a gear spins, it will have a tendency to stay in its current state. This continued spinning, or lack thereof, affects the motion of a gear.

Moment of Inertia

The moment of inertia is defined as: $$I=\int r^2 dm$$

The closer mass is located to the axis of rotation, the lower the moment of inertia, and the easier it is for the object to spin.

The following formula assumes that the gear has constant density and can be approximated as a cylinder. $$I_{gear}=\frac{1}{2}mr^2$$

Most Vex gears are half an inch wide and are made of 7075-T6 Aluminum. We can use this to find the mass of the gear in terms of the tooth count of the gear. Using the formula above in the “positioning” section, we can also find the radius of the gear in terms of tooth count.

| Equation | Comment |

|---|---|

| $$D=M/V$$ | definition of density |

| $$M=D*V$$ | mass formula |

| $$d=T/dp$$ | gear diameter formula |

| $$d=0.0254*T/dp$$ | gear diameter formula in meters |

| $$r=0.0254*T/2dp$$ | gear radius formula in meters |

| $$V=\pi r^2 h$$ | volume of a cylinder |

| $$M=D*\pi r^2 h$$ | mass of a cylinder |

| $$M=D*\pi (0.0254*T/2dp)^2 h$$ | mass of a gear |

| $$M=D\pi h \frac{0.0254^2*T^2}{4dp^2}$$ | simplified |

| $$D=2810\ kg/m^3$$ | density of 7075 |

| $$h=0.0127$$ | thickness of a gear |

| $$M= \left( \frac{T^2}{55*dp^2} \right)$$ | substitution and simplification |

The mass of a gear is the square of the tooth count divided by the product of 55 and the square of the diametral pitch. This means that the moment of inertia ($kgm^2$) of a gear is:

$$I_{gear}=\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{T^2}{55dp^2} \right)\left(\frac{0.0254T}{2dp} \right)^2$$ $$I_{gear}=\left( \frac{T}{28.7dp} \right)^4$$

Inertia in Reductions

From before we have: $$\omega_1=-\frac{T_2}{T_1}\omega_2$$ $$\tau_2=-\frac{r_2}{r_1}\tau_1$$

Derivative with respect to time: $$\alpha_1=-\frac{T_2}{T_1}\alpha_2$$

By definition: $$\tau=I\alpha$$ $$r=T/2dp$$

Substituting: $$\tau_1=I_1\alpha_1$$ $$\tau_2=I_2\alpha_2$$ $$I_2\alpha_2=-\frac{r_2}{r_1}I_1\alpha_1$$ $$I_2\alpha_2=-\frac{T_2/2dp}{T_1/2dp}I_1\alpha_1$$ $$I_2\alpha_2=-\frac{T_2}{T_1}I_1\alpha_1$$ $$I_2\alpha_2=-\frac{T_2}{T_1}I_1* \left( -\frac{T_2}{T_1}\alpha_2 \right)$$ $$I_2\alpha_2=\left( \frac{T_2}{T_1} \right)^2I_1 \alpha_2$$ $$I_2=\left( \frac{T_2}{T_1} \right)^2I_1$$ $$I_1=\left( \frac{T_1}{T_2} \right)^2I_2$$

Since the apparent moment of inertia is directly proportional to the square of the reduction, this derivation shows us that gear reductions allow inputs to drive systems with much larger moments as if they were small moments. In other words, reductions can help move a large flywheel with ease.

Although gears do add inertia to a system, it is typically small in comparison to the benefit of the reduction.

Taking into account the inertia of the gears themselves: $$I_{in}=\left( \frac{T_1}{T_2} \right)^2(I_{out}+I_{G2}) + I_{G1}$$ $$I_{out}=\left( I_{in}-I_{G1} \right) \left( \frac{T_2}{T_1} \right)^2-I_{G2}$$

Generalizing:

2 stages:

$$I_{out}=\left( \left[\left( I_{in}-I_{G1} \right) \left( \frac{T_2}{T_1} \right)^2-I_{G2}\right]-I_{G3} \right) \left( \frac{T_4}{T_3} \right)^2-I_{G4}$$

$$I_{out}=\left( \left( I_{in}-I_{G1} \right) \left( \frac{T_2}{T_1} \right)^2-I_{G2}-I_{G3} \right) \left( \frac{T_4}{T_3} \right)^2-I_{G4}$$

$$I_{out}= \left( I_{in}-I_{G1} \right) \left( \frac{T_2}{T_1} \right)^2\left( \frac{T_4}{T_3} \right)^2-I_{G2}\left( \frac{T_4}{T_3} \right)^2-I_{G3} \left( \frac{T_4}{T_3} \right)^2-I_{G4}$$

3 stages:

$$I_{out}=\left( \left( I_{in}-I_{G1} \right) \left( \frac{T_2}{T_1} \right)^2\left( \frac{T_4}{T_3} \right)^2-I_{G2}\left( \frac{T_4}{T_3} \right)^2-I_{G3} \left( \frac{T_4}{T_3} \right)^2-I_{G4}-I_{G5} \right) \left( \frac{T_6}{T_5} \right)^2-I_{G6}$$

$$I_{out}= \left( I_{in}-I_{G1} \right) \left( \frac{T_2}{T_1} \right)^2\left( \frac{T_4}{T_3} \right)^2\left( \frac{T_6}{T_5} \right)^2-I_{G2}\left( \frac{T_4}{T_3} \right)^2\left( \frac{T_6}{T_5} \right)^2-I_{G3} \left( \frac{T_4}{T_3} \right)^2\left( \frac{T_6}{T_5} \right)^2-I_{G4}\left( \frac{T_6}{T_5} \right)^2-I_{G5}\left( \frac{T_6}{T_5} \right)^2 -I_{G6}$$

n/2 stages:

$$I_{out}=(I_{in}-I_1)\prod_{j=1}^{n/2}\left( \frac{T_{2j}}{T_{2j-1}} \right) ^2-\sum_{i=1}^{n/2}(I_{2i}+I_{2i+1})\prod_{j=i+1}^{n/2} \left( \frac{T_{2j}}{T_{2j-1}} \right) ^2-I_n$$